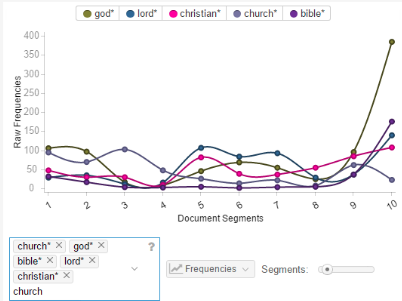

Use of religious language throughout the Anti-Slavery Almanac.

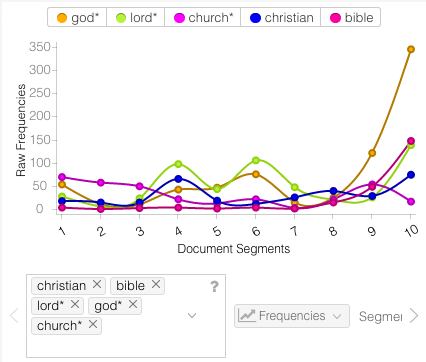

Use of religious language throughout sermons on slavery from the same time period.

The above images represent text analyses of two bodies of data. The first image is a text analysis of the frequencies of the words “god”, “lord”, “church”, “christian”, and “bible” within the corpus of the Anti-Slavery Almanac. The second image is a text analysis of the same words within a collection of sermons on slavery from the same period.

We chose to examine these specific words because they provided the most significant insight into the use of religious language through each body of text. We were interested with this data visualization in exploring the frequency with which religious language was used while discussing the topics of abolitionism and slavery. The abolitionist movement is often thought of as being intertwined with religiosity, particularly with the Quaker communities in the North. In order to test this assumption, we wanted to compare the overtly religious abolitionist speech of the sermons with the more secular abolitionist literature of the Anti-Slavery Almanac.

We were surprised by our findings. The graphs produced by each body of data are strikingly similar for each individual word. In the text analysis for the Anti-Slavery Almanac, the use of each of the five words remains fairly consistent for the most part. The most intriguing features of the graph coming near document segment 4, where each individual religious word dips to a low point, signalling a sharp decrease in the use of religious language about 2/5 of the way through the collection, and at the very end of the collection, from document segments 8-10, where use of the each of these words (besides “church”, which saw a slight decline) increases sharply, particularly “god”, the use of which increases by 300 between document segment 8 and document segment 10. In the text analysis for the collection of sermons, the use of each of the five words remains fairly consistent, with spikes for each word at various places, such as “god” and “lord” rising together near document segments 4 and 6. Similarly to the text analysis for the Anti-Slavery Almanac, within the body of text for the sermons, the use of each word rose considerably between document segments 8-10, with the exception of “church”, which saw a slight decline.

These results showed us that, whether the message was delivered with overtly religious overtones or from a more secular perspective, use of religious language in abolitionist conversation stays relatively consistent. This could be a product of a time in which religious and secular life were more closely intertwined, or it could be symptomatic of the fact that the abolitionist movement originally grew from religious groups.

An interesting topic for future research could focus on the the sharp spike in the use of religious language at the end of each body of text. Further exploration and analysis of these sections of the text could reveal reasons as to why these spikes exists. These spikes come historically late in each data set, closer to the onset of the inevitable Civil War, which may have led to increased use of religious words and rhetoric.