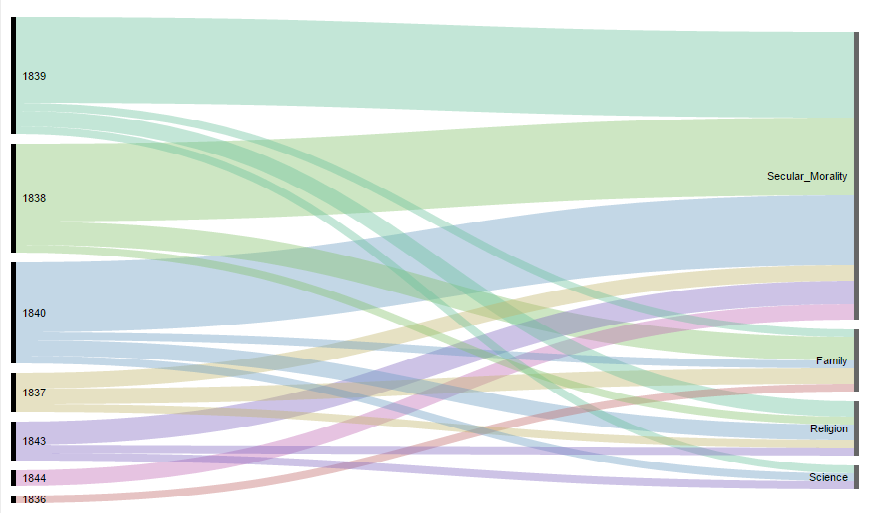

After finding some interesting things in our Voyant data visualization in relation to rhetoric over time, we decided to delve a little further into this idea using RAWGraphs. We used the same themes as seen in our first RAWGraphs tutorial, and also our Palladio visualization. We wanted to see if there were any significant changes in the types of rhetoric more or less frequently used within the Anti-Slavery as time went by.

Our ultimate results were relatively inconclusive in direct relationship to the question we originally set out to answer. The varying sizes of material within each year didn’t allow for perfect comparison between years, and the relatively small number of years within the data set didn’t provide us with enough evidence to reach much of a significant conclusion to our original research question. However, we were able to recognize and view some interesting patterns. Unlike our first RAW Graphs visualization, we were able to see which types of rhetoric were most pervasive throughout the entire data set, as opposed to within each genre category. Originally, we really expected religious rhetoric to have a large presence within our data set. We knew from our first visualization that rhetoric regarding secular morality, not religion, was the most frequently used form within our data set. However, by examining this data visualization, we could see that religious rhetoric was not even the second-most used form of rhetoric across the entire data set. In fact, after secular morality, rhetoric centering on family ties was most frequently seen.

We also expected to see a slight rise in the use of religious rhetoric over time, believing that this would be consistent with our text analysis in the Voyant visualization. The sharp incline in the use of specific religious words toward the chronological end of the data set led us to believe that more pieces written with distinctly religious rhetorical overtones would be located in that section of the collection. However, given the graph above, we have no reason to believe that this is absolutely the case. It would take more quantified analysis of our data set to completely answer that question. It is also possible that a spike in the use of religious words may not always necessitate a rise in religion as an overall rhetorical overtone for individual pieces. While some pieces may reference terms like “bible”, “church”, or even “christian”, their overall rhetorical strategy may lean in other directions.

If given more time and freedom with this data set, this graphical representation could potentially grow into something than answers even deeper questions about the written rhetoric of the abolitionist movement. Potentially expanding the data set to include abolitionist publications besides the Anti-Slavery Almanac throughout a slightly larger date range than the 1836-1844 awarded to us by this collection would allow us to garner a more holistic view of the movement as a whole. From this, we may be able to make some substantial claims about types of rhetoric, changes in rhetoric over time, and rhetorical strategies within the literature of the abolitionist movement.